Trump Defends Saudi Crown Prince as Sacklers Pay $7 Billion in Opioid Settlement

On November 17, 2025, the White House became the unlikely stage for two seismic American reckonings—one rooted in justice for a murdered journalist, the other in accountability for a pharmaceutical empire that helped ignite a national epidemic. While President Donald J. Trump welcomed Mohammed bin Salman, the Crown Prince of Saudi Arabia, with a military flyover and ceremonial honors, he simultaneously dismissed U.S. intelligence conclusions that the prince ordered the 2018 killing of journalist Jamal Khashoggi. Hours later, in a courtroom in White Plains, New York, U.S. Bankruptcy Judge Robert D. Drain signed off on the largest corporate settlement in U.S. history: a $7 billion agreement to dismantle Purdue Pharma L.P. and hold the Sackler family accountable for fueling the opioid crisis that has claimed over half a million lives.

A State Visit Amidst a Moral Paradox

The ceremony for Mohammed bin Salman was meticulously staged: F-35s screamed overhead, cavalry units carried the flags of two nations, and Trump greeted him as "Your loyal highness." But beneath the pageantry, the tension was palpable. Journalists pressed the Crown Prince on the 2018 murder of Jamal Khashoggi, a U.S. resident and Washington Post columnist whose dismemberment inside the Saudi consulate in Istanbul was confirmed by the CIA as having been ordered by the prince himself. Trump, however, offered a defense that blurred moral lines: "A lot of people didn't like that gentleman that you're talking about. Whether you like him or didn't like him, things happened." The president’s remarks echoed his 2018 stance after the killing, when he prioritized arms deals and oil interests over human rights. This time, the context was sharper: the U.S. Senate was hours away from voting on the Khashoggi Records Act (S.J.Res.5), legislation that would force the declassification of all U.S. government files on the murder. Trump had publicly pledged to sign it—even as he privately dismissed its significance. "Even once that happens, though, the release of all of the government's files is not guaranteed," he told reporters, a caveat that left human rights advocates stunned.The Sacklers’ $7 Billion Reckoning

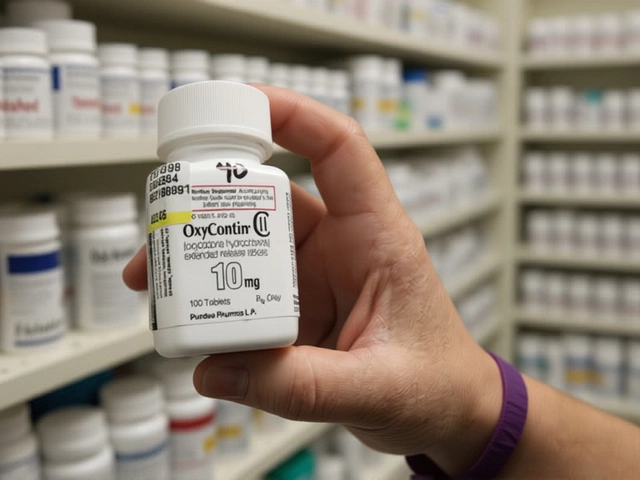

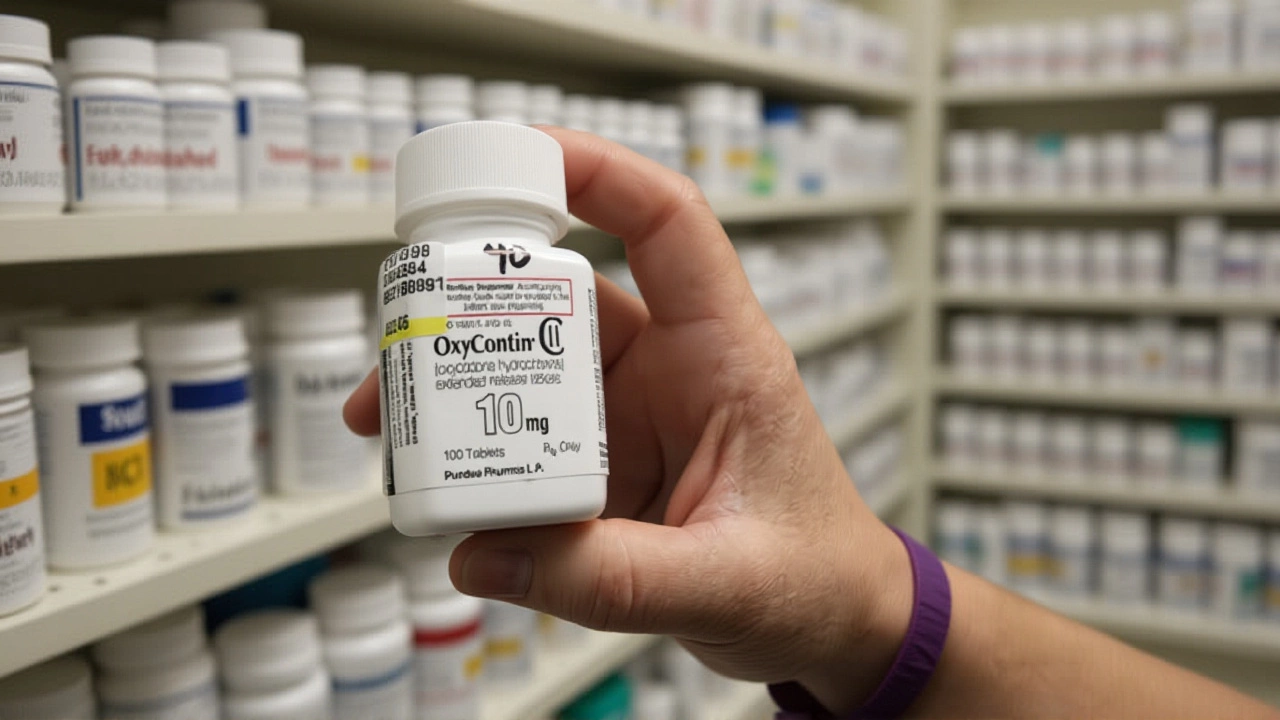

While the world watched the Saudi state visit, a quieter but far more consequential drama unfolded in the federal bankruptcy court. Judge Drain approved the dissolution of Purdue Pharma L.P., the Stamford, Connecticut-based company that, since 1996, aggressively marketed OxyContin as "non-addictive" despite internal documents proving otherwise. The settlement, the culmination of over two decades of litigation, requires the Sackler family—including survivors Jonathan D. Sackler, Kathe A. Sackler, and David Sackler—to pay up to $7 billion over nine years. That’s more than the combined fines of Big Tobacco, Volkswagen, and Enron in their respective scandals. The money will be distributed as follows: $3.75 billion to 50 U.S. states, $1.5 billion to 350 federally recognized Native American tribes, $1.25 billion to hospitals and healthcare systems, and $500 million to approximately 150,000 individuals and families who lost loved ones to overdose. Payments begin January 15, 2026, and end December 31, 2034. Purdue Pharma will cease to exist. In its place, a new public benefit corporation, Knoa Pharma, will be formed, with all future profits from opioid addiction treatments funneled into state-level prevention and recovery programs. The settlement overturns a 2020 DOJ agreement that was struck down by Judge Judith Levy for ignoring victims’ rights. This time, the court ensured individual claimants had a voice. "This isn’t about forgiveness," said attorney Lisa K. Brown, who represented 12,000 families in the settlement. "It’s about acknowledging that profit was prioritized over people. And now, the price has been paid."

Why This Matters Beyond the Numbers

The opioid crisis didn’t start with Purdue Pharma—but it exploded because of it. In 2010, opioid deaths in the U.S. stood at 21,095. By 2022, that number had soared to 81,806, according to CDC data. The Sacklers, once among the wealthiest families in America, became symbols of corporate greed masked as philanthropy. They donated millions to museums, universities, and hospitals—while their company flooded communities with pills. In small towns from West Virginia to Oklahoma, pharmacies became the new corner stores. Doctors, incentivized by Purdue’s sales reps, prescribed OxyContin like candy. And when the pills ran out, many turned to heroin. Then fentanyl. The $7 billion settlement, while historic, won’t bring back the dead. It won’t erase the trauma of children who lost parents, or spouses who buried their partners in their 30s. But it does mark a rare moment when corporate power was held to account—not just by regulators, but by the collective will of thousands of grieving families.What Comes Next?

The Senate votes on the Khashoggi Records Act (S.J.Res.5) on November 20, 2025. Trump has said he’ll sign it. But the Office of the Director of National Intelligence has already signaled that certain intelligence sources and methods will remain classified under Section 6. That means the full truth—names, wiretap transcripts, internal Saudi communications—may never see daylight. For victims’ families, it’s a bitter compromise: partial transparency, but no justice. Meanwhile, Knoa Pharma’s first board meeting is scheduled for February 2026. Critics worry the new entity could become a loophole—a way for the Sacklers to retain influence under a different name. But the settlement’s terms are ironclad: no Sackler can sit on the board. No profits can go to them. And every dollar must serve recovery.

The Double Standard in American Justice

There’s a chilling contrast here. One man, accused of ordering a journalist’s murder, is feted with military honors and defended by the president. Another family, accused of profiting from mass death, is forced to surrender their fortune and legacy. Why does one receive a state dinner, and the other, a courtroom verdict? It’s not just about law. It’s about power. And the uncomfortable truth: in Washington, some crimes are forgiven for the sake of alliances. Others, for the sake of public outrage, are punished.Frequently Asked Questions

How much will each opioid victim actually receive from the $7 billion settlement?

Individual victims and families are set to receive $500 million collectively, meaning the average payout per claimant is roughly $3,300—though many will receive more based on severity of loss, medical costs, or number of dependents. The distribution is being managed by a court-appointed committee, with priority given to those who lost loved ones to overdose or incurred substantial addiction treatment expenses.

Why is the Sackler family allowed to keep any money at all?

The settlement includes a liability release: in exchange for paying $7 billion and giving up ownership of Purdue Pharma, the Sacklers are shielded from future civil lawsuits. This was a hard compromise—many victims’ advocates opposed it, arguing it lets the wealthy escape accountability. But without the deal, the bankruptcy court feared the Sacklers would declare personal bankruptcy, leaving nothing for victims. The $7 billion is still the largest ever paid by a family in U.S. history.

What’s the connection between the Khashoggi Records Act and the Purdue settlement?

There’s no legal link—but symbolically, both represent America’s fractured sense of justice. One case involves a foreign leader accused of murder, shielded by political expediency. The other involves domestic corporate crime, punished only after years of public pressure. Both happened on the same day, forcing a national reckoning: when does accountability matter, and when is it sacrificed for power?

Will Knoa Pharma be truly independent from the Sacklers?

Yes. The settlement legally bars any Sackler family member from holding any position, owning shares, or influencing Knoa Pharma’s operations. The board will be appointed by a coalition of state attorneys general and public health experts. Profits must be reinvested into addiction treatment, prevention, and overdose reversal programs. Independent auditors will monitor compliance annually.

What happened to the $8.3 billion DOJ settlement from 2020?

That deal, which included Purdue Pharma pleading guilty to three federal crimes, was overturned in 2021 by Judge Judith Levy, who ruled it violated the rights of individual victims who weren’t consulted. The new $7 billion settlement was crafted specifically to include victims directly in negotiations—making it legally stronger and more ethically defensible.

Can the U.S. government still prosecute the Sacklers criminally after this settlement?

Yes. The settlement only covers civil liability. Criminal charges remain possible, though the Department of Justice has not indicated any intent to pursue them. Legal experts say political pressure and the complexity of proving individual criminal intent make prosecution unlikely—despite evidence that some Sacklers were aware of Purdue’s deceptive marketing practices as early as 2007.